Implantable sensor detects ovarian cancer early

Patients with ovarian cancer have a 92% five-year survival rate if they are diagnosed at stage I. But a lack of effective screening methods and absence of symptoms in its early stages makes ovarian cancer particularly difficult to catch before it spreads. Patients and clinicians need a kind of internal alarm system, a device that can detect and communicate the presence of cancer cells in the body before they have a chance to inflict damage.

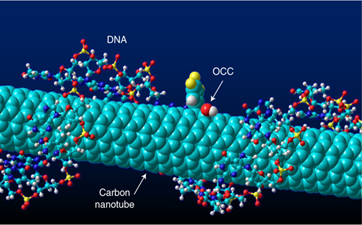

“This may sound like science fiction, but we’re working to make it reality,” says former Damon Runyon Fellow Daniel Heller, PhD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. The Heller lab is developing a tiny, implantable sensor, known as a carbon nanotube, that can detect cancer-associated proteins in the bloodstream and release a signal to a device worn outside the body. This wearable technology would function something like a fitness tracker, collecting and analyzing physiological data without requiring blood tests and biopsies.

To design the sensor, the team is relying on ovarian cancer biomarkers, or distinctive proteins released by ovarian cancer cells. The carbon nanotube would be implanted in the uterus or the fallopian tubes, where the concentration of these proteins is highest, and attached to an antibody that can bind the protein of interest. If this binding occurs, the light emitted by the nanotube would change color, sending a signal that could be picked up outside the body.

The Heller lab has already demonstrated their nanosensor can detect ovarian cancer in mice, and is now conducting their first tests in human uteri that have been removed during surgery. If successful, the carbon nanotube could serve as a rapid screening tool for patients with higher genetic risk of ovarian cancer. It would also benefit patients undergoing cancer treatment, enabling them to monitor disease progression without frequent trips to the doctor or anxious waiting periods between scans. “Right now, it’s hard to tell if a patient has an aggressive cancer or if it’s safe to wait a while before another scan,” Dr. Heller says. “If you could see a change in biomarker levels in hours or days, it could give physicians an earlier warning.”

While the team is current focused on ovarian cancer detection, their nanosensor technology may one day be designed to recognize other biomarkers as well—providing life-saving early warnings for patients across cancer types.