Potential new targeted therapy for a rare but lethal cancer

Adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) is a rare but aggressive cancer that usually develops in the salivary glands and is often diagnosed in younger adults. Because of its rarity, ACC has received relatively little attention from cancer researchers, and as a result, there are no approved therapies for the disease.

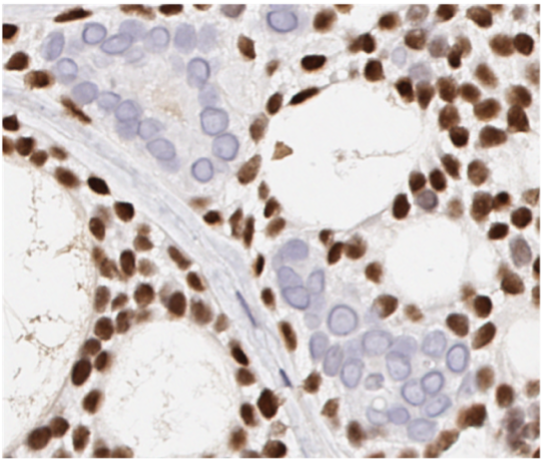

and ductal-like cells (blue)

But recently, former Damon Runyon-Rachleff Innovator Piero D. Dalerba, MD, and his colleagues at Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center made a discovery about ACC that could lead to the first targeted treatment. It had been observed that ACC tumors contain two distinct subtypes of cancer cells, characterized by their appearance: myoepithelial-like cells, which are thin and spindle-shaped, and ductal-like cells, which are rounder. Using cutting-edge RNA sequencing techniques, Dr. Dalerba and his team studied the molecular differences between the two subtypes to find out how each arose within the tumor. As it turns out, the relationship between the two subtypes is not that of neighbors but that of parent and offspring, the ductal-like cells evolving from the myoepithelial-cells. When populated by a mix of the two types, ACC tumors tend to grow slowly. Once ductal-like cells acquire dominance, the cancer becomes more aggressive.

Fueled by this discovery, the team probed further to identify—and ultimately block—the cellular signals involved in the transition from myoepithelial-like to ductal-like. Observing both animal models and three-dimensional lab-grown tumor models, they determined that the transition is driven by retinoids, chemical compounds derived from vitamin A. Excitingly, they found that administering a drug to suppress retinoid signaling selectively killed the ductal-like cells. While such a drug would not eliminate the tumor altogether, it could prevent aggressive, late-stage disease, a potentially lifesaving intervention.

The team is now working to develop clinical therapies from these findings.

“We have preclinical evidence that the drugs are active,” says Dr. Dalerba. “Our dream is to bring them into clinical trials and test them for antitumor activity in patients."

This research was published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.